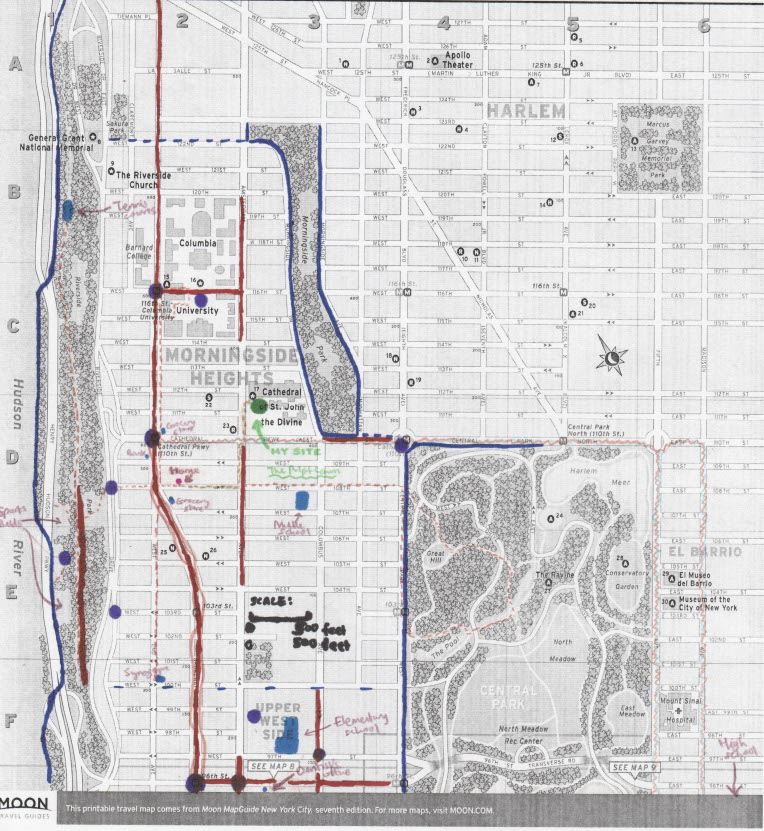

For this assignment, I’ve situated my chosen location of the pulpit lawn at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine within the broader neighborhood that surrounds it inside Manhattan, New York City. This also happens to be the neighborhood I consider home; as can be displayed in the map, the apartment where I live is a short distance from the cathedral, and the path that I take to walk between those sites is in the orange-green dotted line. The neighborhood boundaries that I provide here (marked in dark blue) are based on my own perceptions and my associations with certain places; in such a densely populated and complex place as Manhattan, there is no doubt whatsoever that another person near an edge of my outlined neighborhood would consider an entirely new set of edges, as defined by Kevin Lynch’s notion of the elements of an urban neighborhood. Even the parks don’t provide obvious edges, as can be shown by the fact that I included Riverside Park (to the west) in my neighborhood but not Morningside Park or Central Park, as a result of my sense of the people and communities that I perceive to frequent these parks. I would argue that in New York the edges tend to be relatively sharply defined but not definitive in the slightest.

What do I mean by this? There are many structures, such as parks, rivers, wide avenues, and broad school or housing campuses, that create barriers and can have the effect of dramatically differentiating one city block or one stretch of an avenue from another. To take an example, the people who live on Amsterdam Avenue and West End Avenue (say in the stretch from 104th Street to 107th Street) are WORLDS away from one another, in terms of class, race, age, and simply based on with whom people form community. These particular divisions, which are some of the least egregious in New York, call to mind Kenneth Jackson’s description of redlining in cities, and make me wonder whether there were lines drawn between these areas that prevented more intermixing. But although many of these boundaries may exist, there are so many and they overlap in so many ways that it would be impossible to map out clear-cut sections that everyone could agree on. The area bounded in dark blue is what I consider to be “my neighborhood” because it contains many of the places I frequent and because the edges I chose constitute existing barriers outside of which I associate myself with it less, but there are probably at least 50 different sub-communities and a person from each sub-community would define their neighborhood using a different set of barriers that also clearly exist. There are probably hundreds of natural “edges” within the boundaries of my neighborhood and I just happened to choose a set that makes sense to me.

However, given the way I decided to demarcate things, the cathedral (and my site specifically) is close to an edge provided by the western side of Morningside Park. There is in fact a steep hill upon which the cathedral sits, which descends rapidly to the east beginning at the entrance to the park on its west side. This is probably one reason why the edge is so well-defined here; this side of Morningside Park is rather prohibitive to all but the most determined walkers entering from the west side. But the cathedral campus is really much more open to those entering from Amsterdam Avenue to its west, rather than Morningside Drive, which is itself significantly lower in elevation than St. John the Divine and from which one would look up 25 feet and see largely black fencing. The cathedral’s famous facade faces instead towards Amsterdam, as does the main entryway to the close. There is a very grand set of stone steps leading up to the cathedral’s main entrance that would have made William Whyte proud because of its great sitting potential; however, interestingly, the steps are rarely used, only occasionally occupied by some dining university students or by a family of tourists taking a brief rest.

This section of Amsterdam Avenue is relatively quiet, the area to the north being highly trafficked by Columbia students and the area to the south home to the center of a robust Hispanic community. These highly-walked roads, described as “paths” by Lynch, are demarcated in red marker on my map. Other paths in my neighborhood include a popular stretch of walking space in Riverside Park, a small shopping district on Columbus Avenue south of 100th Street, and the entirety of Broadway, which is the default conduit and central hub of the neighborhood, the place where every community in the vicinity comes together and interacts. Many of the neighborhood’s “nodes” (marked in purple, and denoting a junction and/or concentration of paths) are located on this street, and indeed the entirety of Broadway may be appropriately described as a node.

But the cathedral, while not in truth very far from Broadway geographically, is neither the site of many paths, nor is it really a node in comparison to the places that surround it. In contrast, it gives off an atmosphere of distance, even reclusion from the bustling city life. But this is a fiction, in a sense. The precise reason why I chose the pulpit lawn is its strong function as a node: the place where everyone from the summer camp gathers at the beginning and end of the day, parents swarming to the same place to pick up their kids and then dispersing once again throughout the neighborhood. Placed in relative contrast to the city’s high activity, the pulpit lawn is not as concentrated, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a significant place because of its role as a junction where paths cross. My site is one of perhaps 10,000 nodes in the neighborhood: dozens of schools, dozens of camps, dozens of community centers, and sports fields, and coffee shops, and youth hostels, and religious centers. There are just so many, from so many overlapping communities, that most don’t stand out above any of the others.

There’s a reason that for one final element of the neighborhood Lynch proposes, “landmarks,” I didn’t even try to include “commonly agreed-upon” landmarks. In my opinion, they don’t exist. These kinds of things are much more dependent upon the places that you might go to, so I put in blue the “landmarks” that are unique to me: how I might situate myself in my neighborhood, where I might meet up with people, and what locations stand out to me when I think of my neighborhood. And the orange dotted lines are paths that I take frequently, even if they are not the most common paths in the neighborhood. I feel content that my map reflects one kind of representation of the neighborhood I live in -- maybe not a universal one, or even one that any single other person might replicate, but one that can accurately describe a sliver of a lived experience in this section of New York City.

Neighborhood map:

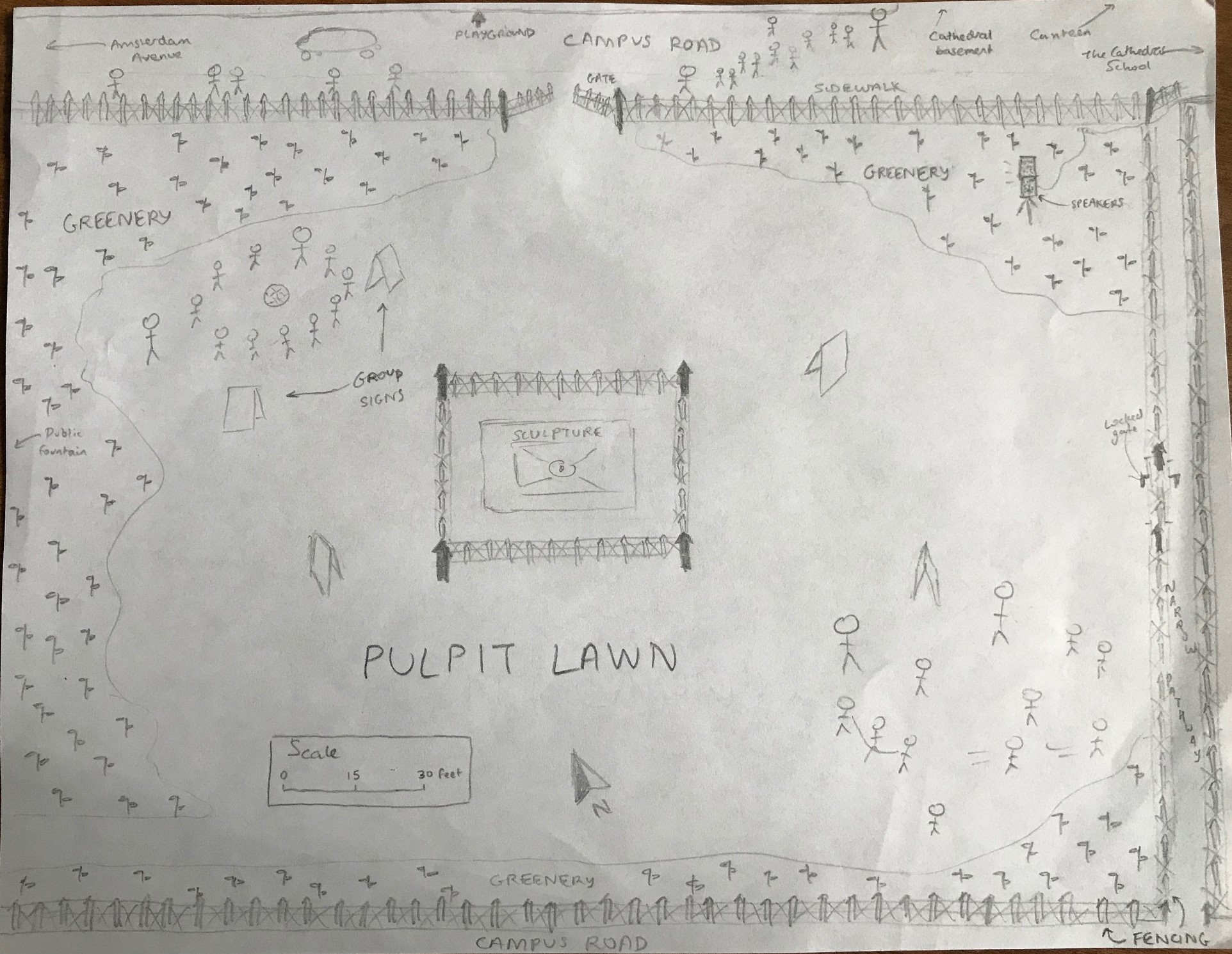

Map of my original site: